31 July, 2013

Internal Movement: Free Movement of Persons

Response From Migration Watch UK

Summary

1. EU competence develops over time and, in practice, is irreversible. The addition of a dozen new members with a total population of about 100 million and a standard of living of roughly a quarter of the EU 15 is, combined with the free movement of labour, placing increasing strains on wealthier members – notably Germany, the UK and the Netherlands.

2. Britain is almost uniquely vulnerable. The presence of one million migrants from the A8 is a significant “pull factor” for further migration. Our benefit system is based on residence, requiring no history of contributions, and tax credits (designed to lift children out of poverty) are a huge incentive to low paid migration.

3. The effect of EU competence is to open this benefit system to EU workers, almost from arrival. A worker from Romania or Bulgaria with a spouse and two children would, even on the minimum wage in the UK, receive take home pay eight or nine times that which he or she would earn at home after allowing for the difference in the cost of living. A single such worker would earn five times as much as at home. The benefit to the GDP per head of British residents would be negligible.

4. Restricting access to benefits for five years is a minimum requirement to reduce these incentives but would entail a very difficult negotiation with EU partners and the Commission.

Context

5. When the UK – alongside Ireland and Denmark - joined the European Community in 1973 it was a community of six Western European countries designed to facilitate trade between members. Over the years the powers of the EC/EU have grown as has its membership. It now comprises 28 countries of varying size and economic performance with a total population of over 500 million.

6. As the EU has grown in size, both geographically and institutionally, so has the power that it wields over members. Successive treaties, secondary legislation, directives and case law are binding on member states which cannot subsequently repatriate the powers concerned.

7. This ever evolving process, often resulting in further loss of national control, is an important consideration in assessing present competencies. With specific regard to free movement, the relationship today is very different to the past and may well be very different to how it will look in the future. Indeed, it must be assumed that UK control over migration matters will be further eroded. Of particular concern is the possible accession of Turkey. The Turkish economy is growing quite fast but there are still huge numbers of poor, especially in the East who could form a major wave of migration; by the time of accession, Turkey could have a population of 80 - 100 million.

EU Free Movement

8. The principle of free movement of labour is one of the four pillars of the common market, established in the Treaty of Rome signed in 1957. It allows for nationals to take up employment across the Union and take their families with them. This was originally free movement of labour, not all citizens.

9. What the EU is now moving to is, in effect, free movement of all persons, regardless of economic activity or inactivity. Successive changes have expanded free movement to include students, self-employed people, self-sufficient people and job seekers. This is a clear departure from the original principle of free movement of labour.

Implications for the UK of EU Legislation on Free Movement of Persons

10. EU legislation on the free movement of persons as well as social security harmonisation has always prevented the UK from controlling EU migration. However, net migration from the EU15 has not been particularly significant. Between 1997 and 2011 it averaged 24,000 per year and reached a high of 38,000 in 2004. Overall it amounted to less than 30% of net foreign immigration.

11. It is net migration from the A8 that has transformed the picture. The census has demonstrated serious discrepancies in the net migration estimates of A8 migrants that render them unreliable. However, the population estimates show that the A8 population in the UK has increased by around 100,000 per year since 2004.

12. As the government seeks to bring total net migration to the UK down to acceptable and sustainable levels it is targeting non-EU migrants since they are the only group that can be controlled through the immigration rules. As non-EU migration falls, EU migration as a proportion of total net migration will increase.

Social Security

13. This situation is exacerbated by the present EU regime on social security. Social security and free movement are intricately connected. Social security provision for EU citizens was intended to ensure that EU nationals wishing to work in other EU member states were not disincentivised from doing so as a result of national social security rules.

14. This principle has also been stretched to the limit. All EU citizens are now supposed to have free and full access to the welfare state of other countries in exactly the same manner as nationals of those countries. In the context of the UK, where entitlement is based on residency rather than contribution, this in effect allows EU citizens to enter the UK and claim benefits almost on arrival so long as they can demonstrate that the UK is their “centre of interest”.[1]

15. There remains one thin line giving some protection to the UK welfare state - the ‘right to reside’ element of the Habitual Residence Test which limits access to certain benefits. EU nationals have a right to reside if they are exercising their treaty rights as a worker, student, self-employed person, self-sufficient person, or a job seeker. British nationals satisfy this test by fact of their citizenship. However, the European Commission has opened an infringement procedure against this test on the basis that it “indirectly discriminates against non-UK nationals coming from other EU Member States and thus contravenes EU law.”[2] The UK government has not amended the legislation in line with Commission request and the matter has now been referred to the European Court of Justice for adjudication. If the UK is unsuccessful at the ECJ the implication is that all EU citizens will be able to move to the UK and become resident immediately thus gaining immediate access to benefits.

16. Meanwhile, there is a particular problem over the EU requirement to pay child benefit to children still resident in their home country but at the level of benefits in the country where the worker is employed.

17. The extent to which EU workers draw benefits in the UK cannot be accurately determined as the nationality of recipients is not recorded. This will be corrected when Universal Benefit is introduced nationwide.

18. It is however often claimed that migrants are far less likely to claim benefits than UK nationals. This appears to be based on a DWP study which omitted tax credits, as well as Housing and Council Tax Benefit[3]. In addition, the DWP study was carried out in February 2011 when EU nationals from the A8 generally had to work for at least 12 months before getting access to job-seekers allowance and other benefits. These restrictions on access to benefits for A8 migrants were lifted in May 2011[4]; now all benefits can be claimed almost immediately on arrival (see paragraphs 14 and 15).

19. The UK is uniquely attractive to migrants from Eastern Europe because our system of tax credits heavily favours those in low paid work. Restricting access to both benefits and in-work tax credits would significantly reduce the incentive to migrate from some of the poorer countries in Eastern Europe, where wages are far lower and the social security system does not significantly increase the wages of the low paid.

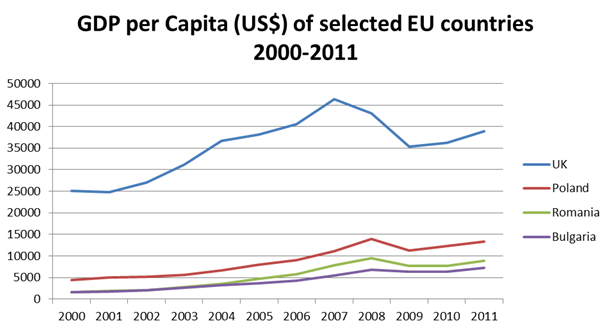

Figure 1. GDP per Capita of Selected A8 and A2 countries, 2000-2011. Source: World Bank.

20. The benefits and tax credit regime significantly boost the wages of migrants from East Europe most of whom are low paid. For example, a single person in Poland working at the minimum wage would have a weekly take home pay of £98. Moving to the UK and taking a job at the minimum wage would increase his wage by two and a half times to £254 once the costs of living have been accounted for. However, were that person to be denied access to the welfare state for five years (on the grounds that he had not contributed anything in income tax and national insurance) he would only be able to earn just under twice what he could at home. Similarly, Polish families are able to substantially increase their wage by moving to the UK, earning almost four times as much as they would at home. However, were the incentive of benefits not available then the increase would be significantly less, especially for families. Romanian and Bulgarian nationals would able to increase their take home pay by a factor of five or eight, as outlined in the table below.

Table 1. Table of Incentives to Migrate to the UK

| Table of Incentives to Migrate to the UK, Weekly Take Home Pay at Minimum Wage | ||||||

| In Home Country after Tax with Benefits | >In UK after Tax with Benefits | > In UK after Tax without Benefits | ||||

| Single Person | Worker & Spouse + 2 children | Single Person | Worker & Spouse + 2 children | Single Person | Worker & Spouse + 2 children | |

| Poland | £98 | £145 | £254 | £543 | £184 | £184 |

| Romania | £55 | £70 | £254 | £543 | £184 | £184 |

| Bulgaria | £49 | £62 | £254 | £543 | £184 | £184 |

21. East European migration has been of great benefit to individual employers by providing very low paid workers who are also very industrious and flexible. However, according to a study by the NIESR, their contribution to GDP per head in the medium term is likely to be “negligible”.[5]

Policy Options to address tension between EU legislation and effective immigration control.

a. Opt-out of principle of free movement

22. The UK could seek to achieve an opt-out from the principle of free movement of persons while remaining committed to the other principles of the free movement, goods, services and capital. This would not be negotiable. Nor is it necessarily desirable. The UK needs to remain open to talented people from across the EU. There are also over 400,000 British people exercising their treaty rights by working in other EU countries and another half a million people living but not working across Europe.[6]

b. Better enforcement of habitual residence test

23. The UK could enforce the rules that already exist more effectively. The Habitual Residence Test[7] which acts as the gateway to the welfare state is poorly policed. The test is an on-going one for recent EU migrants and should be better enforced in stages, as laid down in EU legislation. For example, all EU citizens have treaty rights which grant them the right to move for a three month period to any EU country, regardless of their economic status. After this initial three months EU citizens then have to prove that they are exercising one of their treaty rights, i.e. as a worker, student, self-employed worker or self-sufficient individual. If they do not fall into one of these categories they should lose their right to reside and therefore any claim to any sort of welfare benefit. If they cannot provide for themselves without recourse to welfare then they should be encouraged to go home. If, however, EU citizens are exercising another treaty right, as jobseekers, the treaty allows them to do so for up to six months. If after this period an individual has not found work his right to reside should end. Access to all benefits should also be terminated. This will require better coordination with local authorities who currently decide on applications for social housing, housing benefit and Council tax benefit. Anyone who does not have a right to reside and who cannot live without financial support from the welfare state, should be helped to go home.

24. All of the above is allowed, and indeed stipulated, in the various treaties and would simply be a case of enforcing the rules. In order to implement such a system, EU citizens would have to register with the police or Home Office if they wished to remain in the UK after three months thus allowing the various authorities to enforce the right to reside test at various stages of residency. A similar system is operational in Spain whereby an EU national must register his presence if he wishes to remain beyond three months.[8]

25. This would ensure than the benefits system is not abused however it does not address the key issue, which is that access to the benefits system for EU citizens can provide a huge economic incentive to migrate to the UK, especially from the less wealthy Eastern European states.

c. Restricting access to the welfare state for probationary period

26. The UK could seek to negotiate a deal whereby EU citizens maintained their treaty rights as workers, students etc., but would not have access to social security benefits or tax credits for a period of five years, bringing the regime for access into line with that for non-EU citizens. This would be a challenging task but the UK could expect some support from other countries which have had a similar experience of EU migration, such as Germany and the Netherlands.[9]

Conclusion

27. The effect of EU competence on the free movement of persons is to leave the UK open to very substantial migration of workers from Eastern European member states. The scope for a renegotiation that does not undermine the single market is limited to restricting access to benefits but even that will, in practice, be difficult to achieve.