Summary (for a shorter summary of this paper click here).

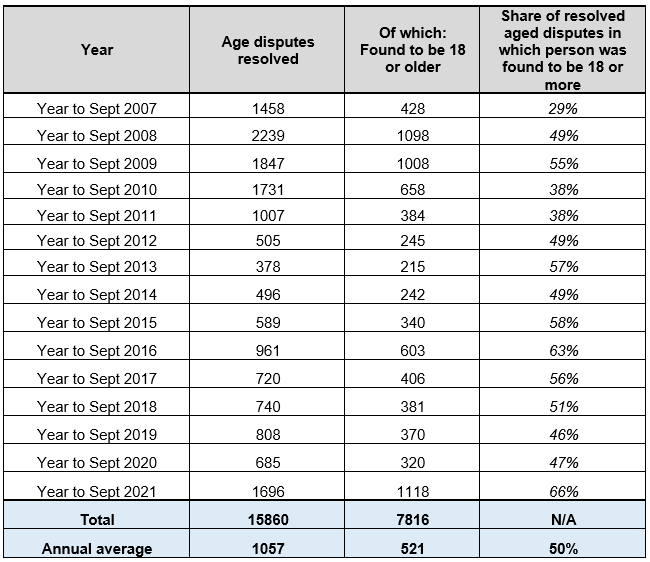

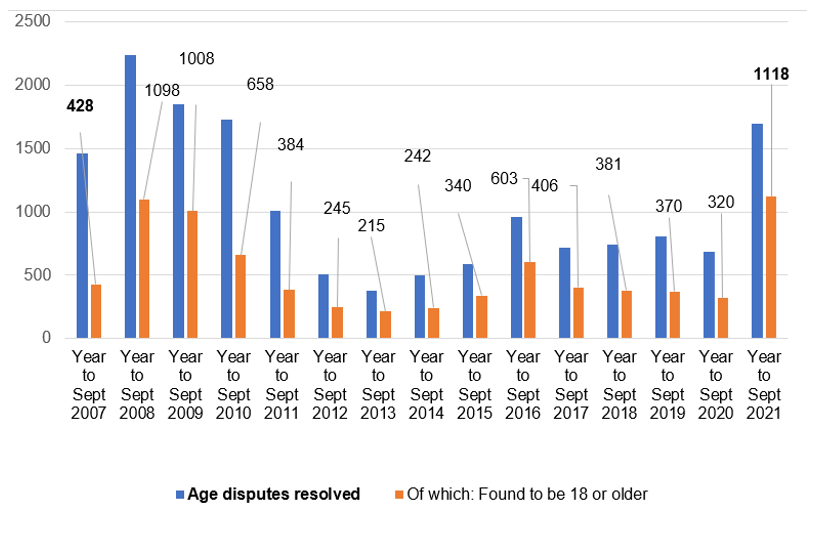

1. The system for checking the age of asylum claimants is so loose that it gives the benefit of the doubt to those saying without proof that they are minors. In the midst of this, there has been a major rise in asylum fraud by adults pretending to be children, with two in three (66%) concluded disputes in the year to September 2021 revealing that the person was 18 or over (1,118 people). This is the largest numerical total since published records begin in 2006, and is 3.5 times the number for the previous year (320 – Annex A below). The huge rise is likely linked to rocketing illegal Channel crossings by boat this year (see our Channel Tracking Station). Quarter 3 of 2021 – when dinghy arrivals surged – saw the highest quarterly number of age disputes recorded (904), well above the previous 2006 high (679). Many arrivals destroy documents, making it harder for age and identity to be verified. There are grave safety concerns since adults who falsely claim to be minors are placed alongside vulnerable young people in schools and housing. However, the government has remarkably conceded that bogus ‘children’ could continue to be placed with minors for an initial period even if ‘doubt still remains as to their claim to be a child’. For the sake of child safety, the government must ensure no one is placed among children if those conducting initial assessments have doubts about the person’s age.

Introduction

2. Under the present rules, there are incentives for adult asylum seekers to be treated as children. Those deemed to be minors can benefit in various ways, including the housing and support they receive, the treatment of their asylum or immigration claim by the authorities, the arrangements that would need to be made to secure their removal from the UK (where they do not establish a lawful basis to stay) and rules regarding the use of immigration detention for children. We have seen a great deal of abuse of these provisions. There is a worrying degree of scope for people who are not children to be treated as minors – and placed alongside vulnerable young people – until a further Merton test (by social workers) attempts to establish the veracity of their claimed age.

3. One of the key problems with the laxity of the system as it stands is that it provides too much scope for abuse especially at an early stage. Current Home Office guidance states that a decision should only be made to treat the claimant as an adult if two officers – one at least with the grade of Chief Immigration Officer, Higher Executive Officer or Higher Officer – have independently assessed that the claimant is an adult because their physical appearance and demeanor very strongly suggest they are 25 or over. If this test is not met but the immigration officials do not accept the claimed age, the individual will be given the benefit of the doubt and provisionally treated as a child while being referred to a local authority for the Merton assessment to be carried out.

4. As the government has said, this means that even where an immigration official believes that an individual who is claiming to be a child is as old as 24, they must still treat them as a child, which in practice will mean that the individual can be placed alongside children, pending the outcome of a subsequent assessment. Even then the later Merton test conducted by social workers is far from fool proof (as it is based upon a subjective judgement) although we require more data to establish the degree to which it is or is not being exploited.

5. The age of a person arriving in the UK is normally established from identity documentation. However, as the Channel Threat Commander Dan O’Mahoney told the Home Affairs Select Committee in September 2020, the standard practice among those crossing in boats from Northern France, for example, is to destroy documentation en route. This is often done by migrants in order to obstruct attempts by to identify them upon arrival. In fact, a specific law was passed in 2004 to penalise those who make a claim after destroying documentation i.e. the Asylum and Immigration (Treatment of Claimants Act) 2004. Despite this the government increasingly refuses to prosecute those who do this (see blog).

6. This lax and naive system is also open to be exploited by terrorists. For example, a judge said the Parson’s Green bomber, who injured scores of people in September 2017 when he exploded a bucket bomb on the London Underground, lied about his age when claiming asylum.

7. Finally, there are major financial and fairness implications. On average, taxpayers provide £46,000 each year to local councils to look after each unaccompanied asylum-seeking child. As well as the obvious safety risks, this form of abuse also takes away from support that would otherwise be available to help genuine children.

What do the statistics show?

8. In 2019, the UK received more asylum claims from unaccompanied minors than any other European country, including Greece and Italy. Since 2015, the UK has received, on average, more than 3,000 unaccompanied asylum-seeking children per year. Where age was disputed and resolved from 2016-2020, 54% were found to be adults, according to Home Office statistics. There are indications that this situation is worsening. Home Office statistics (depicted in Figure 1 in Annex A on p. 5 below) show that 66% (1,118 out of 1,696) of those who claimed to be a minor, but whose stated age was subject to dispute and conclusively assessed, were found to be 18 or over during the year ending Q3 2021. Meanwhile, the total number of people found to be adults (1,110) is the highest since available records began in 2006, with the third quarter of 2021 being the largest total in any quarter since the mid-2000s.

9. The rise is likely linked to surging Channel crossings in boats. Quarter 3 2021 saw the highest quarterly totals of both age disputes (904) and those found to be 18+ after assessment (546) since 2006, at the same time as 11,178 people were reported to arrive by dinghy.

10. In contrast to about two-thirds of resolved disputed claims being ruled as adults in the year to September 2021, the corresponding share for the previous year was 47% (320 out of 685) and the annual average from 2006 to 2020 has been half. In total, 7,996 asylum claimants claiming to be children were found to be adults after assessment (2006 to Q3 2021).

Other reports and incidents

11. Concerns about exploitation of child migrant rules have particularly grown since 2016 when the UK witnessed the admission of a number of applicants from Calais refugee camps who claimed to be children but appeared to be much older and arrivals hidden in lorries shot up. In 2017 ex-Border Force boss Tony Smith said: “Some would’ve sworn on their mums’ lives they were 16 despite having a beard and balding.” The danger of mature adults having free access to groups of children is obvious. Even more shocking is the thought that those judged to be 18 or more are given the benefit of the doubt. It is also notable that legal claims from migrants accused of not being honest about their age are costing taxpayers hundreds of thousands of pounds. The cases have arisen when lawyers challenge age checks by social workers. Cases can drag on for as long as three years. A freedom of information release last October (reported in the media) revealed that Kent County Council alone has paid out over £300,000 on 25 cases in the past four years.

12. In one case, a pupil was said to ‘look about 40’ with a receding hairline and was enrolled in a class of 15-year-olds. The asylum seeker was said to have travelled alone to the UK without paperwork, before being placed in a school in Coventry. A girl at the school shared his picture on social networking app Snapchat and questioned his age. The picture was eventually seen by the girl’s mother who raised concerns with the school.

13. The Independent Chief Inspector of Borders recently found that immigration removal centres – e.g. Yarl’s Wood and Brook House – saw an increasing number of age dispute cases from October 2020 (in the midst of a rise in the number of people entering the UK in dinghies via cross-Channel trips), with concerns raised by Home Office and supplier staff, and by the Independent Monitoring Board, about the quality of initial screening at the Kent Intake Unit.

14. There is also a major threat to public security. The current lax system is open to be exploited by terrorists. Parson’s Green bomber Ahmed Hassan said he was a 16-year-old orphan when he entered the UK illegally in 2015 and claimed asylum. Yet the judge who jailed him for life in 2018 said he was certain Hassan lied about being a child to stay here.

The need to tighten up the initial age assessment

15. Although the Nationality and Borders Bill, currently before the House of Lords, makes some welcome improvements – such as formalising the scope for use of scientific evidence and the creation of a new body to assess age – the government appears to have backed off its earlier intention to put tighter initial assessment rules in primary law. The current position means that even where an immigration official believes that an individual who is claiming to be a child to be as old as 24, they must still treat them as a child, which in practice will mean that individual will be placed alongside children for a period of days or weeks.

16. The government had indicated its intention to put in place a more appropriate threshold for initial age assessments. Former Home Office minister Chris Philp told a parliamentary committee in December 2020: “You… have questions around the screening that happens at an earlier stage before you can do a full Merton-compliant assessment, but it does get litigated. The Home Office has social workers who assist local authorities with that process in some cases, particularly in Kent, to try and get it right first time. The gold standard is currently the Merton assessment… One area we are looking at closely is whether we can legislate to clarify better in statute how these age assessment processes work so that we remove some of the ambiguity that currently exists.” And in March 2021, the Home Office stated: “Currently, an individual will be treated as an adult where their physical appearance and demeanour strongly suggests they are ‘over 25 years of age’. We are exploring changing this to ‘significantly over 18 years of age’. Social workers will be able to make straightforward under/over 18 decisions with additional safeguards.”

17. What would the bill do? Part 4 would introduce new processes for age assessment for those who require leave to enter/remain and for whom there is ‘insufficient evidence’ to be sure of their age. The legislation outlines powers and responsibilities on the Secretary of State, local authorities, and ‘designated persons’ to carry out checks, and would formalise permission for “scientific methods” to be used in conducting such assessments (they are reportedly already used by some local authorities). The bill also specifies rights of appeal against such assessments and the use of legal aid for appeals. It provides scope for further age checks if new evidence becomes available. More detailed provisions about the conduct of age assessments are to be set out in regulations subject to the affirmative procedure (see House of Lords Library briefing on the legislation).

18. Although the bill provides scope for further changes to be made via secondary legislation, the government did previously say that it was their ‘intention’ for a provision specifying ‘a more appropriate threshold for initial age assessments’ to be put into primary legislation. However, the present bill includes no such ‘more appropriate provision’.

19. The government has pointed to the fact that, in August 2021, the Supreme Court upheld the Home Office’s previous policy of treating asylum seekers who claim to be children as adults if two Home Office officials think that the person looks significantly over 18 (see R (BF (Eritrea)) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2021] UKSC 38). This policy was subsequently amended in 2019 to the ‘over 25’ rule noted above on the back of a previous Court of Appeal decision. Because of the later 2021 Supreme Court ruling, the government says that it no longer needs to place tougher initial assessment rules in primary law, while adding that it still intends to tighten initial assessment rules. Our view is that, Supreme Court decision or not, the government should put the change into primary legislation in order to make the will of Parliament as abundantly clear on this matter as possible.

20. We were also concerned to read in a subsequent Home Office statement that ‘it remains the Government’s intention that where the individual’s physical appearance and demeanor does not meet that threshold and doubt still remains as to their claim to be a child, it must be assumed that the individual is under 18 unless and until a more comprehensive age assessment is carried out….’ Indeed, there no adequate measures in the bill currently before Parliament that would tighten initial assessments in a manner that would close this loophole. This does not appear to take the safety of vulnerable children seriously enough since it still appears to mean that adults falsely claiming to be children may be placed alongside them until assessments later prove they are actually 18 or older. The government must bring forward reform to tighten initial assessments so child safety is put first and not side-lined.

Proposed introduction of scientific methods to age assessment procedures

21. We welcome the government’s intention to create a robust approach to age assessment to ensure that authorities can act as swiftly as possible to safeguard against adults claiming to be children and to use new scientific methods to improve the ability to accurately assess age. It is notable that the UK is one of the only countries in Europe not to use scientific age assessment methods to help determine a person’s age when they arrive into the country. Various scientific methods are used to assess age in Sweden, Norway, France, Germany and the Netherlands (as well as other countries):

- For instance, in Sweden the National Board of Forensic Medicine (Rättsmedicinalverket) conducts a medical age assessment – a procedure which the person is free to refuse. The result of the assessment is communicated to the Swedish Migration Agency who makes their decision based on the assessment and other evidence presented in the case.

- In Italy medical examinations are used for assessment although the person is free to refuse to participate.

- In Cyprus, an age assessment interview is carried out before referring the person to medical examinations.

- In France, an interview is conducted with a person whose age is unclear and who does not possess identity documents. The interview aims to assess the age and the circumstances of the person concerned. It is carried out by the local authority in the administrative département in which the person is based, or by delegated associate services. If a doubt about the person’s age remains, the individual can be referred to medical examinations, with the person’s consent.

22. We also support the creation of a National Age Assessment Board (NAAB) which we understand will primarily consist of expert social workers dedicated to conducting age assessments. We believe that there is scope for this change to improve the consistency and quality of age tests and minimise the incentive for claimants to be dishonest about their age.

Conclusion

23. We agree with the government’s assessment that the current age assessment process is ‘highly subjective and often subject to prolonged and expensive legal disputes [in which] adult claimants can take advantage of a fragmented system to pass themselves off as children, benefitting from additional protections properly reserved for the most vulnerable’. The proposed reforms will deliver some improvement as they provide scope for rationalising, simplifying and formalising more objective checks against this form of asylum abuse. However, they do not yet sufficiently address the huge loophole in initial assessments which currently risk placing adults alongside vulnerable children for an initial period. In the government’s words: “Many adults claim to be children…we have examples of adults freely entering the UK care and school system, being accommodated and educated with vulnerable children.”[i] Yet the government made a crucial concession in July 2021 when it stated: “Where… doubt still remains as to their claim to be a child, it must be assumed that the individual is under 18 unless and until a more comprehensive age assessment is carried out”. This is deeply unsatisfactory as it suggests a threat to children posed by this form of abuse will continue. The government should set out reform to initial assessments in primary law, as they said they would. This will make the will of Parliament on the matter as abundantly clear as possible. The safety of children, and public security, is at stake.

Annex A

Table 1: Asylum age disputes, Year to September, 2007 to 2021(Home Office figures).

Figure 1: Total resolved age disputes / of which those assessed to be 18+. Home Office data.

[i] Home Office, New Plan for Immigration, March 2021, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/972517/CCS207_CCS0820091708-001_Sovereign_Borders_Web_Accessible.pdf

Note: The Merton Test is a social worker led age assessment – named after the leading case of B v London Borough of Merton [2003] EWHC 1689 (Admin)). The test must adhere to procedures set out in that case and developed in subsequent case law, usually including a number of interviews which explore the person’s background and also consider information obtained from others who have contact with the individual.