On 13 October 2021, the government’s Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) recommended an expansion to the intra-company transfer visa route for overseas workers (primarily in the IT industry) to come and work ‘temporarily’ at the UK branches of companies (this route has run at 55,000 grants to main applicants and dependants per year between 2011 and 2019).

The Committee told Ministers that this much-abused route should now become a direct route to settlement (despite there being no safeguards to ensure UK workers are prioritised for job openings). The Committee also said that there should continue to be NO REQUIREMENT for applicants to be able to speak English. This flies in the face of four in five of UK voters who say English ability is a vital requirement for immigration.

Here is our comment on these proposals. Below is our full evidence which was submitted to the MAC in June 2021.

—–

Our evidence to the Migration Advisory Committee, submitted 15 June 2021

The UK allows mobility of temporary overseas workers under its international obligations linked to the 1995 General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). Since 2009, it has institutionalised such arrangements in intra-Company Transfer (ICT) visa. The government says that the purpose of these arrangements is to accommodate ‘temporary’ moves by key business personnel, enabling multi-national companies to move their workers between subsidiary branches:

- As the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) has previously said, the ways in which the route has been used have been ‘undercutting’ the domestic labour market ‘in the sense that salaries being paid to intra-company transferees are below what would have to be paid to UK resident workers of equivalent quality’. This is out-of-keeping with the government’s stated intention for employers to ‘focus on training and investing in our domestic workforce’[i].

- The route may have had a negative impact on opportunities for British IT workers and computer science graduates. The unemployment rate of Computer Science graduates six months after graduating has been higher than the overall average for all graduates.

- Multinational corporations are being rewarded through tax breaks and allowance rules for their unwillingness to invest in British talent.

- Significant numbers of ICT visas have been issued for third-party contracting – encouraging the exploitation of staff from abroad, at cheaper wages, in a manner that undercuts – and thus harms – domestic competitors.

- It is not accurate to call this visa ‘temporary’ given that it can last as long as nine years, and enables switching into other routes that lead to settlement.

- The Home Office recently said that the route allows companies, among other things, ‘to fill a specific vacancy that cannot be filled by a British or EEA worker’. This is not accurate as there is no resident labour market test (RLMT) attached to the ICT route.

We do not think that retaining this visa route is in the interests of the UK, especially during the current employment situation. However, if retained then it is vital to ensure that any Global Mobility route does not disadvantage UK workers. We recommend the following changes:

- Closing tax loopholes that enable companies to benefit from hiring temporary overseas workers while reforming rules which enable allowances to be treated as part of salary calculations.

- A global mobility route must not further exacerbate the problem of the UK being unable to produce its own homegrown Computer Science graduates, nor should it provide opportunities or incentives for companies to get around the provisions of the new Skilled Worker route (as seems to have occurred with Tier 2 – General).

- To ensure UK jobseekers do not lose out, it would be better to revert to the pre-2009 arrangement where there was an explicit requirement for employers to confirm that their sponsored employees had company-specific knowledge required for the post on offer that could not be provided by a worker in the UK.

- The length of time long-term ICT visa holders can stay should be shortened from five to nine years down to no more than 3 years, while switching into other routes that allow settlement should be stopped. The ICT route has gone far beyond enabling multinational businesses to move their employees temporarily in and out of the UK so that the business can operate most effectively; clearly a visa lasting between five and nine years, and which allows switching into settlement routes, is not ‘temporary’.

The history of Intra-Company Transfer visas

The UK is a party to the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) overseen by the World Trade Organization. This Agreement was created to extend to the service sector the system for merchandise trade set out in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. The GATS came into force in January 1995. Under the GATS, the UK is committed to allowing the temporary presence (for up to three years) of intra-company transferees (ICTs) where:

- they are managers or specialists;

- they are transferred to the UK by a company established in the territory of another WTO member;

- and they are transferred here in the context of the provision of a service through a commercial presence in the UK

The UK has had provisions for such mobility prior to GATS coming into force. These continued under the pre-2009 work permit regime, where there was an explicit requirement for employers to confirm that their sponsored employees had company-specific knowledge and experience required for the post on offer that could not be provided by a worker in the UK.

However, this was replaced by a requirement for only a short period of previous employment with the company, ranging from only three months (for graduate trainees) to only 12 months (for those coming in on a salary of £41,500).

There are currently two main types of ICT:

Long-term staff visa – The minimum salary threshold for this is £41,500. Applicants need to have worked for their employer overseas for more than 12 months, unless the person is paid £73,900 a year or more to work in the UK. The maximum total stay allowed for an intra-company Transfer visa is: 5 years in any 6 year period if the person is paid less than £73,900 a year; 9 years in any 10 year period if the person is paid £73,900 a year or more.

Graduate trainee – For those brought into graduate trainee programmes for specialist roles. Applicants have to be recent graduates and need no more than three months’ experience with the employer overseas. They can stay for up to 12 months and need be paid a minimum salary of only £23,000.

There also used to be a shorter-term visa route which allowed a stay of up to three years, but it was disbanded in 2017. The Home Office licenses organisations to sponsor ICT visa applications.

How many ICTs have been issued per year since 2010/11?

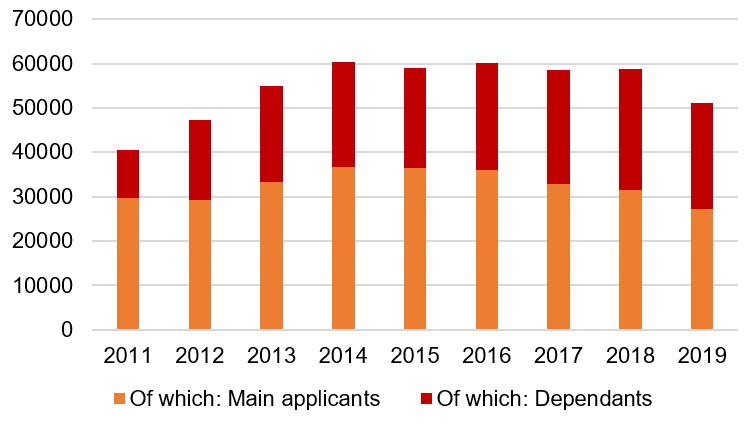

The use of temporary worker visas has grown as a share of total work permits issued. In 1992, such visas accounted for 27% of all work permits issued in that year. By 2017, they accounted for 62% of work permits issued. Total grants of ICT-related visas have run at an average of about 54,600 per year since 2011 – 32,200 for main applicants and 22,400 for dependants. Over this period the proportion of dependants has risen very significantly.

Figure 1: Grants of Tier 2 visas to ICT main applicants and dependants (Home Office entry clerance visa statistics).

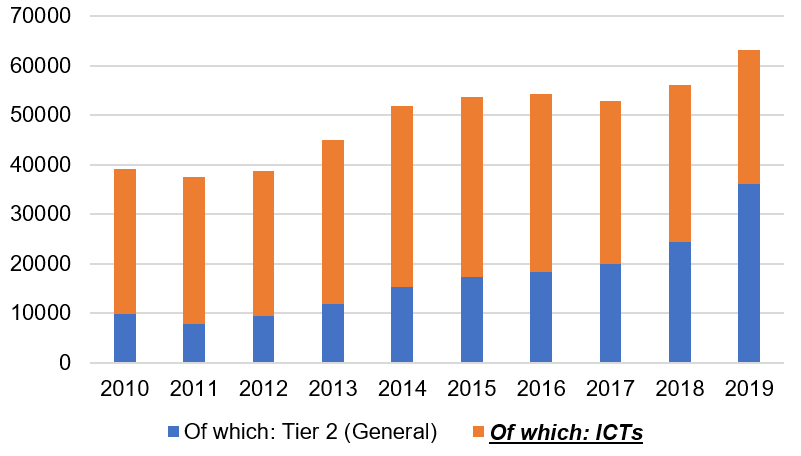

Grants to ICT main applicants accounted for about 60% of total grants to all Tier 2 applicants during that period. Although the proportion appears to have fallen in 2018 and 2019 the reason is likely to be that the removal of health workers from the Tier 2 (General) cap has seen increases in grants for these specified occupation.

Figure 2: Tier 2 entry-clearance grants to main applicants by category, 2010-2019 (Home Office statistics).

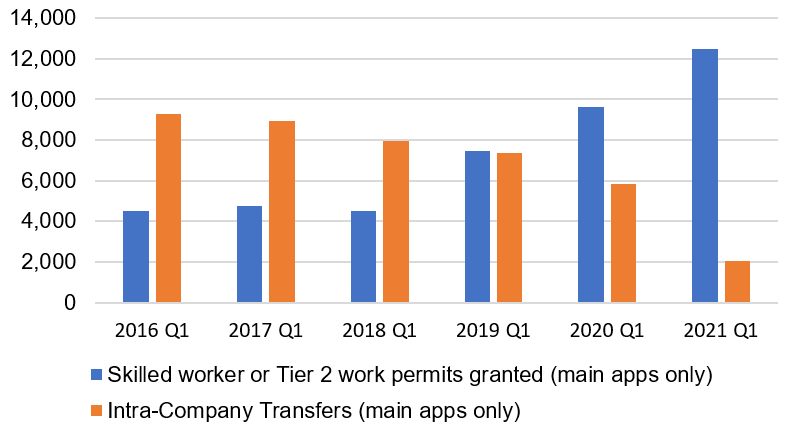

Early figures for entry-clearance work permit grants under the post-Brexit immigration system suggest that a number of those who previously used ICTs may have moved into using Skilled Worker Visas during the last quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021 (due to the much looser rules).

Although more data is required, this suggests that the ICT route may now be largely surplus to the requirements of employers, a number of whom appear to have previously used the ICT route as a means of by-passing the Tier 2 (General) cap that was in place from 2011 until 2020. Other reasons they may have done this, apart from the lack of a cap, are because the ICT route allows the migrant to be seconded to the UK and remain on the payroll of their overseas employer, instead of having to be paid by the UK sponsor. In addition, there is no English language requirement.

Figure 3: Entry clearance grants to main applicants for Tier 2 General / Skilled Worker Visas and Intra-Company Transfer visas (Quarter 1, 2016 – 2021). (Home Office statistics).

The MAC has previously raised a number of concerns about non-conventional ways in which the ICT route was being exploited:

- It strongly recommended that the Government consider improving enforcement and transparency around the ICT route to prevent it being used outside of its intended purpose.[i]

- In 2015 the MAC:

- highlighted serious concerns about the use of the route for third-party contracting and the undercutting of UK resident workers of equivalent quality. Notably it said: “There is a risk that the UK portion of third-party contracting achieves its efficiencies through lower salaries than would have to be paid for equivalent UK workers who would then be undercut by migrants and harmed by the use of the route”.

- It also found that ICT transferees receive very favourable tax breaks and allowances that may be beneficial to both the employer and worker, but which also make it cheaper to employ an immigrant worker than a resident one. It found: “Combined with the tax breaks on offer with allowances, there is a high risk that these provisions are enabling employers to benefit from significant cost savings when employing intra-company transferees compared to UK workers.”

Despite a number of suggestions by the MAC to address the problems noted above, most were not taken up by the government. and the major deficiencies of the ICT visa route have remained in place.

Previous Home Office comments on the ICT route

The Home Office has previously echoed some of the MAC’s findings, noting that ‘sponsors who engage migrants from less developed countries have a market advantage over resident contractors and consultancy service providers who engage resident workers’.

The HO said that this was due to:

- Consultancy type work normally being paid higher than the going rate for a given occupation

- Reduced expenses because migrants can be more easily relocated and have lower expected standards of living in respect to accommodation. In addition, accommodation is often counted as an allowance for a migrant when it would be an expense for a resident worker.

- Tax breaks applied to migrants engaged on the basis of a secondment from an overseas linked company

Because of this, the HO added, ‘these problems may drive down the earning potential of working in the sector, resulting in a reduction in the availability of resident workers as fewer people choose to pursue a career in the sector. This will drive increasing demand for migrant workers from less developed countries that have invested heavily in their IT industries’.

Any reform of the ICT route should address a number of perverse incentives that are causing UK workers to lose out. We summarise these problems below:

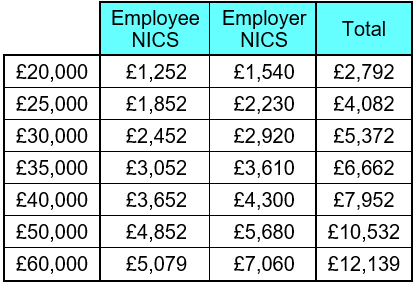

a) Tax breaks which help harm the prospects of UK workers

Intra-company transferees that can retain a non-domiciled status are exempt from UK income tax. Additionally, allowances included within the total salary offer are not subject to income tax for the first two years for intra-company transfers. Finally, ICT migrants are exempt from national insurance contributions in the first year of their stay. The table below details the potential savings for an employer resulting from this latter exemption, depending upon the salary of the respective employee. Because of these tax breaks, which effectively encourage companies to employ workers from overseas, a UK resident worker would need to earn considerably more than the current ICT salary thresholds in order to obtain the same net pay as ICT transferee (at least in the first year of their residence). In the words of the MAC: “The exemption from employer’s national insurance contributions means that third party contractors gain a competitive advantage over domestic firms in terms of total labour costs.”

Table 1: National Insurance Contribution savings over a year for particular salary levels (Rates and allowances for 2020/21 from HMRC).

b) The use of ICTs for third party contracting which was not one of its intended purposes

Third-party contracting involves multinational companies obtaining contracts (usually in the IT sector) from UK-based private companies or public sector organisations and delivering those contracts by bringing in a workforce from another country (usually India). Such client contract ICTs constitute the majority of all ICTs issued. The MAC has said that one problem with this is that ‘intra-company transferees coming in under a third-party contract are paid significantly less than within the conventional use of the route, suggesting they do not possess such highly specialised skills’

Elsewhere, the MAC stated: “Many firms employing migrants – particularly those employing Indian information technology workers on third party contracts – make rather modest efforts to upskill UK workers’ adding that ‘this use of the route disadvantages IT firms within the UK who do not have access to this source of labour and UK workers in the IT sector’. Allowing contractors to put in low bids for business on the basis that they can bring in people from abroad at a lower cost undercuts competitors with a domestic workforce and affects the wages of professionals in that sector generally. Salaries paid to ICTs are below what would have to be paid to UK resident workers of equivalent quality. Nor, as the MAC has noted, is third party contracting contributing to the stock of IT skills within the resident UK workforce.

It is notable that during a recent five year period, of all ICTs issued by 644 companies, 23,440 (66%) were for third-party client contracts, of which 17,035 (73%) were used by just eight companies using 1,000 ICTs or more. There is a direct relationship between the scale of a company’s issue of ICTs and the likelihood of their being used for the purpose of third-party contracting.

c) Allowance arrangements that encourage undercutting

Although tightened up in April 2017, ICTs can still receive an accommodation allowance as part of their salary. This is a maximum of 30% of salary for long-term ICTs and 40% for graduate trainees. In addition, business expenses for travel, accommodation and subsistence are exempt from income tax for the first 24 months of a posting. The MAC is correct to note that such arrangements allow multinational corporations to save money by hiring overseas instead of investing in UK talent

d) ICT use for third-party contracting discourages the UK’s young people from entering the IT industry

There has been a decline in the number of students within Higher Education studying Information and Communication Technology subjects. The MAC has also said that it did not see direct evidence of the claim by employers that they were providing training to UK residents.

Recommendations

If this route is to remain in place as part of the new immigration system, it is necessary to reform it considerably so that the misuse by companies documented so ably by the MAC and others in the past can be rooted out. Most certainly such distortion must not be encouraged by the way in which the route is formulated (as is presently the case):

- ICT length of stay should be shortened – In line with GATS international obligations, ICT visa holders should only be able to stay in the UK for three years maximum (rather than the present five to nine years) while switching into other routes that enable settlement should be curtailed.

- Rules to check on worker experience and resident labour availability should be strengthened – To safeguard resident workers, especially during this challenging period, it would be better to revert to the previous arrangement where there was a requirement for employers to confirm that their sponsored employees have company-specific knowledge and experience required for the post on offer that could not be provided by a worker in the UK.

- Tax breaks for companies hiring ‘temporary workers’ should be closed – Workers coming in on ICTs, as well as the companies that employ them, should be required to pay National Insurance contributions regardless of how short the period they are in the UK, as to do otherwise is a clear distortion of the labour market that rewards employers for using foreign workers. Income tax loopholes should also be closed.

- ICT qualifying times should be lengthened – The qualifying time that ICT applicants must have worked for their company overseas should be restored for all applicants and increased from twelve months to two years (with an exemption for graduate trainees) in order to ensure that the route is used by experienced staff and managers, as originally intended.

- Use of ICTs for third-party contracting should not be permitted – There is evidence that the ICT route is being used in the IT sector to replace UK workers on cost grounds, either by helping to relocate the work overseas or by filling UK based jobs with overseas workers. The use of ICT visas for third-party contracting should not be permitted, especially in light of the much looser arrangements now pertaining in the new Skilled Worker Route which threaten both to displace and undercut UK resident workers.

- Allowances should not contribute towards the salary threshold. Companies currently have a financial incentive to hire an ICT rather than a UK worker and are encouraged to replace UK workers on cost grounds. To help address this, expenses and accommodation considerations should be removed from salary calculations of ICT applicants.

- English language tests should be extended to ICT applicants – Currently only those extending their leave in the UK to beyond three years are subject to an English language requirement. This should be extended to all applicants at the independent advanced level (B2).

Conclusions

It is essential that the immigration system helps to ensure that both government and employers and companies do more to train up and encourage British young people to go into the IT industry and also that they invest much more in recruiting UK workers of all backgrounds, paying them decent wages and get better at retaining them by offering them attractive and flexible working conditions. It is clearly wrong for the government to provide incentives, via the tax system and abstruse allowance arrangements, for large companies to hire workers from abroad while disadvantaging workers of all backgrounds here in the UK. Allowing contractors to put in low bids for business on the basis that they can bring in people from overseas at a lower cost undercuts competitors that have a domestic workforce and affects the wages of professionals in that sector generally. The ICT route as it is currently constituted also appears to be hollowing out the stock of domestic IT skills. If the ICT route is retained going forward, it is imperative to ensure that such arrangements do not entrench such problems, especially during the current very serious economic and unemployment crises.