Response to UCL paper on the fiscal effects of immigration to the UK

30 December, 2014

Summary

Overall cost of migration

1. Between 1995 and 2011 the fiscal cost of migrants in the UK was at least £115 billion and possibly as much as £160 billion according to a report from the Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration headed by Professor Christian Dustmann at University College, London. The report found that migrants in the UK were a fiscal cost in every year examined.[1]

Contribution of ‘recent migrants’

2. The report claims that migrants who had arrived in the UK since 2000 had made positive contributions throughout the period from 2001 to 2011. This does not appear to be correct, the figures in the paper show that the contribution from these recent migrants was negative in each year after 2008.

Contribution of ‘recent A10 migrants’

3. The authors also highlighted a finding that between 2001 and 2011 recent migrants from Eastern Europe had made a net contribution of £5bn. While this correctly reports their most optimistic finding, their calculations in four alternative scenarios were all lower. One of these alone was enough to reduce the contribution to as little as £0.066bn – a sum within the margin of error of such calculations.

4. In addition, the very large fiscal cost of immigration overall is compounded by the cost of congestion and loss of amenity caused by our rapidly rising population.

Introduction5. CReAM have now formally published a revised version of a discussion paper first put out in November 2013 on the fiscal effects of immigration to the UK.

6. The original paper was carefully assessed by Migration Watch[2] and others[3] who challenged a number of their assumptions and calculations. Some of the suggestions have been taken up in the revised paper but others have been ignored. CReAM looked at the fiscal contribution of migrants between 1995 and 2011. Their new paper highlights their findings that

- Immigrants from the EEA had overall made a positive fiscal contribution

- The contribution of recent immigrants (i.e. those that arrived since 2000) was positive with recent immigrants from the A10 countries of Eastern Europe making a positive contribution of £5 billion while those from the EU15 made a contribution of £15 billion

- In contrast British born (‘natives’) were found to have cost nearly £600 billion over the same period.

7. The paper and accompanying press release does not highlight the finding that the overall cost of migrants in the UK was between £115bn and £159 bn – significantly greater than their previous finding of £95 bn and a span that would include the Migration Watch estimate of £148bn. Even in the period after 2000 when recent migrants were claimed to have been contributing significant amounts the costs were found to be £88 bn.

8. The headline figures presented were the best case scenarios. Four alternative scenarios with different assumptions affecting the amount of taxes paid - described as ‘robustness checks’ were contained in an Annex. All increased the cost of migration for every group in every period. This suggests that the headline findings are not in fact robust and certainly not conservative.

General observations

9. The Migration Watch assessment of the original discussion paper noted that, on the authors’ own findings, there was no positive fiscal impact from migration in any year. It further pointed out that applying general simplifying methodologies to the specific migrant groups that they had singled out would result in consistent upward bias in their calculation of migrant contributions.

10. In this context, the claims by the authors that their work had produced – in contrast to all previous research – ‘precise’ and ‘robust’ estimates seemed inappropriate. We are pleased to see that these assertions no longer appear in the final version of the paper. This is an area where there is consensus on the broad methodology to be followed i.e. what should be taken into account in an assessment of fiscal impact. But all earlier work had highlighted gaps in the data and the difficulty of establishing matters with any degree of certainty.

11. Nonetheless, the finding of CReAM in their final paper is still that immigration has resulted in a high fiscal cost to the UK over the whole period from 1995-2011 and that there has not been a positive contribution in any year. Nor has there been a positive contribution ‘throughout’ from recent migrants as the authors now claim.

Overall fiscal costs of immigration – CreAM findings

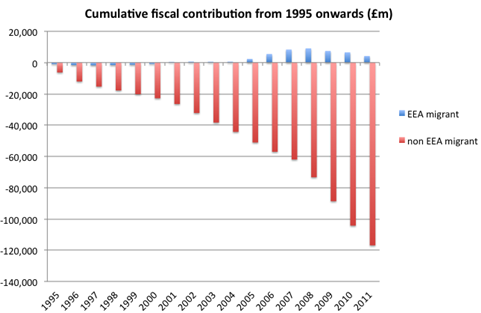

12. The introduction to the final paper states that EEA migrants have made a positive contribution and that non-EEA migrants have made a negative contribution. This does not make clear that the non EEA negative contribution was nearly thirty times greater than the EEA positive contribution, and that the overall fiscal cost during the period resulting from immigration to the UK was – on their own calculations - over £115bn. The following bar charts illustrate their findings:

Figure 1

13. Selecting particular groups by place of origin or time period can be misleading. While a positive cumulative contribution might have been reported for EEA migrants, not only is this very small in comparison to the overall cost, but it occurred in the past; the annual EEA contribution was negative after 2008.

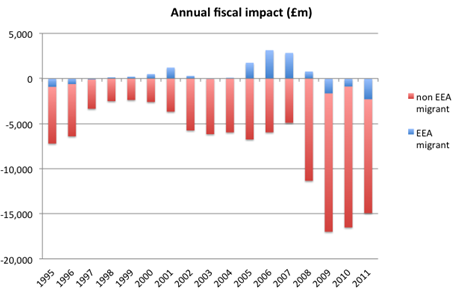

Figure 2

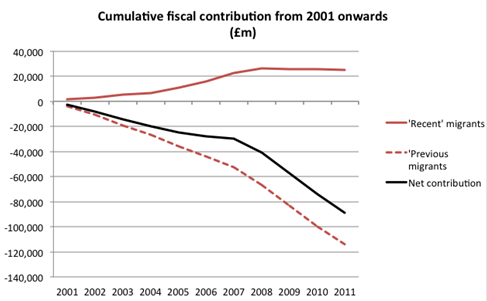

14. Further, looking only at a positive cumulative contribution by recent EEA migrants does not by any means imply that further EEA migration will have an even more positive impact. Quite the opposite. Breaking down the annual figures shows clearly that positive contributions from recent arrivals were not maintained throughout the eleven year period and have not compensated for the increasing fiscal costs of earlier arrivals. It is notable that only recent arrivals from the EU15 (and other EEA - comprising Iceland, Lichtenstein, Norway and Switzerland) appear to have maintained a positive fiscal balance, but also that even this contribution is small in the overall balance, as shown in the graph from their figures below.

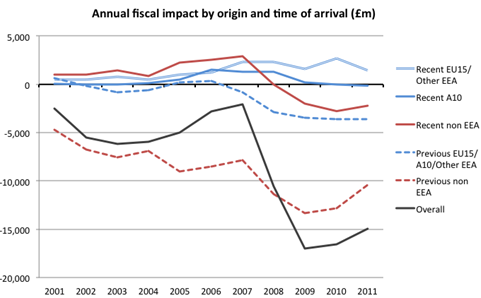

Figure 3

15. While the authors do concede that migrants arriving in the UK before 2001 have been and remain a significant fiscal cost to the UK, their narrative implies that the migrant population can be simply divided into a newly-arrived group of young working-age people and a much older group who have been in the UK for many years and are understandably no longer contributing quite as much as the most recent arrivals. The authors say, for example, that their calculation will include people who came to Britain in 1950 but only what they paid into the state and took out in benefits and public services after 1995 (and by implication disregarding a lifetime of contribution).

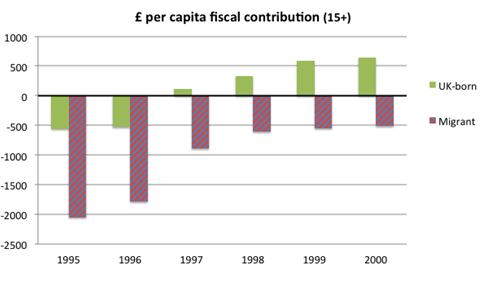

16. However, that argument applies with even greater force to the UK-born population, which includes to a far greater extent people whose years of contribution during a working life are behind them and who are now a high cost to the state through pensions and healthcare. This is illustrated in Table 3 of their paper by a higher average age in every year for the UK-born population and by the finding that the migrant groups were far less likely to be receiving state pensions. Yet looking at the period up until 2001 the per capita fiscal contribution of the UK-born was consistently higher than that of the migrant population, which was negative in all years, including years in which the UK-born were making a positive contribution – as shown in the bar chart from their figures below.

Figure 4

17. The suggestion that migrants from 2001 onwards are making up for the shortfall resulting from previous migration (including of course those arriving as recently as 2000) can be examined by looking at the cost over the remainder of period from 2001 onwards. In that year, previous migrants – i.e. all of those who had arrived up until 2001 – had a net fiscal cost of £4bn. Those who arrived that year made a net fiscal contribution of £1bn and in the eight years before recession hit in 2008 their contributions, together with those of subsequent arrivals, had added up to a total of £26bn. After this nothing more was added to the pot by them or further subsequent arrivals. But the cost of previous migrants increased far more, adding up to £66bn over the pre-recessionary period, for a net cost overall of £40bn, and subsequently by a further £50bn during which period no contribution was made by the more recent arrivals, for a total net cost between 2001 and 2011 of nearly £90bn, illustrated below in Figure 5. And this of course is on the most optimistic of the authors’ assumptions.

Figure 5

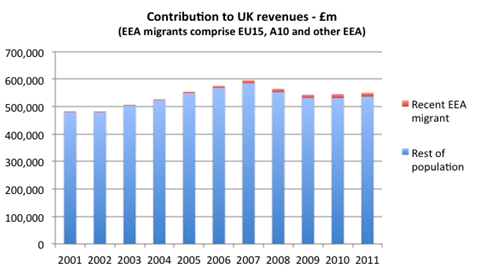

18. Finally, any apparent increasing contribution also has to be seen in the context of overall revenues and of increasing numbers of people. The authors provide multiple charts illustrating various ratios of revenues to expenditures that do not really illustrate this. For example, the contribution to revenues claimed to have been made by recent EEA migrants between 2001 and 2011 was a very small part of total government revenues.

Figure 6

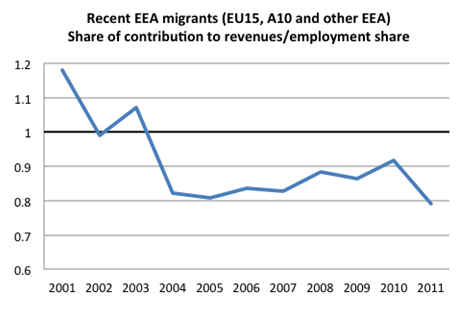

19. And of course the increase over the period derives from increasing numbers of EEA migrants in employment in the UK. Comparing the share of revenues contributed by recent EEA migrants to their share of people in employment, not only are they contributing less than the average worker in revenues, but in 2011 their relative contribution per worker to revenues was less than in any previous year.

Figure 7

Assumptions underpinning the CReAM findings

20. Migration Watch raised a number of issues with the authors about the methodology and assumptions made in their original discussion paper. The key ones were:

- Income should be taken into account in estimating means-tested benefits (including tax credits). No account at all has been taken of this in the final paper with the likely result that the headline and alternative scenarios all under-estimate migrant costs.

- Attribution of company taxes by simple population share will distort the contribution of recent migrants. This continues to be the basis of the headline findings, with an alternative assumption relegated to ‘robustness checks’ that considerably reduces all migrant contributions.

- Employee wage data from the LFS is unlikely to be a sufficient basis for any precise estimation of personal taxes. The headline findings again appear unchanged. An alternative assumption in the ‘robustness checks’ does now estimate income for the self-employed separately, based on income and tax data for the self-employed. This reduces the contribution of all migrants, but particularly those of recent EU15/Other EEA and recent non EEA groups. However, they do this by treating everyone within each industry sector as earning the same. So the most recently arrived self-employed migrant is treated as earning the same as life-long residents. This is entirely unsound as it presumes not only no difference between migrant and UK-born incomes, but also that the most recently arrived self-employed earn as much from their first day of arrival in the UK as those with long-established businesses. For this reason, even the lower numbers in the alternative scenario appear to over-estimate migrant contributions.

- Business rates should not be attributed to self-employed individuals. In the headline findings these have now been attributed on the basis of population share. While this is some improvement it still assumes that even the most recently arrived migrants have an equal stake in UK business assets compared to lifelong residents. The alternative assumption that they do not begin to acquire such assets until after ten years of residence has been used in the ‘robustness checks’ with considerable reductions in all migrant contributions. This adjustment alone reduces the overall fiscal contribution by recent A10 migrants essentially to nothing.

- There are significant characteristics of migrants generally or specific groups that are likely to make a difference to fiscal impact (for example location/housing benefit, age/inheritance tax, remittances/consumption taxes, family size/tax credits). In the headline findings account has been taken of variation in housing benefits only. Account has been taken of the possible effect of remittances on indirect taxes in one ‘robustness check’ scenario, and this considerably reduces the contributions of all migrant groups.

21. It appears that a further issue has been raised on their calculations of indirect taxes. While the authors appear to accept in their narrative that their original methodology will actually give an incorrect result they seem to have repeated this in their headline findings and relegated a more accurate result to their ‘robustness checks’, which particularly reduces the contribution of recent migrant groups.

‘Robustness checks’

22. The point of a robustness check is to vary assumptions to see whether they make any difference to the reported findings. If they do not make much difference, then that is an indication that the initial results are likely to be correct. For both average cost and marginal cost calculations, the authors provide four different variant assumptions for the calculation of revenues and one for the calculation of expenditures. The results of these – detailed in Table A7 of the paper – are quite different from their reported findings. In particular,

- the headline positive results for recent non-EEA migrants turn negative in all four revenue scenarios

- the headline positive results for recent A10 migrants are reduced in all scenarios

- the headline positive results for recent other EEA migrants are reduced in all four revenue scenarios.

23. The following table shows the difference between the reported findings (average cost of pure public services) and the alternative revenue scenarios. Negative figures represent increases in fiscal cost in £m.

Table 1

| Effect on reported fiscal contribution 2001-2011 of applying alternative scenario (£ million) | Recent A10 | Recent EU 15 and other EEA | Recent non EEA | All recent migrant |

| a) including self-employed income in personal tax calculation | -564 | -3497 | -12630 | -16691 |

| b) including self-employment and pension income in indirect tax calculations | -1408 | -3258 | -13718 | -18384 |

| c) assuming remittances mean lower spending in UK so less indirect tax paid | -2890 | -1886 | -8350 | -13126 |

| d) assuming recent migrants not paying corporate taxes through investment stake in UK plc | -4895 | -2713 | -15122 | -22730 |

24. Further, it also appears that each of the row results in Table A7 represents the adjustment of a single factor in the calculations leading to the headline result. If so, this means that it does not fully illustrate the range of possible results, as the varying assumptions are not mutually exclusive. To establish the likely true range of possible outcomes the cumulative impact needs to be reported.

25. However, even taking these robustness checks at face-value, they are in the context of reported findings of a total £25bn positive contribution by recent migrants. Each individual robustness check reduces this by at least half and one by as much as 90%. Robustness checks that reduce the reported values to this extent, suggest that the headline results are not in fact robust at all. It is also noteworthy that each alternative revenue scenario reduces the fiscal contribution of each recent migrant group. Thus clearly suggesting that, not only are the headline results not robust, but that they are still highly likely to be overestimates and that the degree of overestimation could still be considerable.

Footnotes

- URL: http://www.cream-migration.org/files/FiscalEJ.pdf

- Migration Watch UK ‘An Assessment of the Fiscal Effects of Immigration to the UK’, March 2014, http://www.migrationwatchuk.org/briefing-paper/1.37

- Nigel Williams, ‘Responding to ‘the Fiscal Effects of Migration to the UK’, December 2013, http://www.civitas.org.uk/pdf/RespondingtotheFiscalEffects.pdf; Mervyn Stone, ‘Plain Assumptions and Unexplained Wizardry Called in Aid of ‘The Fiscal Effects of Immigration to the UK’, December 2013 http://www.civitas.org.uk/pdf/assumptionsandwizardry.pdf; Robert Rowthorn ‘A Note on Dustmann and Frattini’s Estimates of the Fiscal Impact of UK Immigration’, April 2014 http://www.civitas.org.uk/pdf/rowthorndustmannfrattini.pdf; Robert Rowthorn ‘Large-scale Immigration-Its economic and demographic consequences for the UK’, August 2014 http://www.civitas.org.uk/pdf/LargescaleImmigration.pdf

- URL: http://www.cream-migration.org/files/FiscalEJ.pdf

- Migration Watch UK ‘An Assessment of the Fiscal Effects of Immigration to the UK’, March 2014, http://www.migrationwatchuk.org/briefing-paper/1.37

- Nigel Williams, ‘Responding to ‘the Fiscal Effects of Migration to the UK’, December 2013, http://www.civitas.org.uk/pdf/RespondingtotheFiscalEffects.pdf; Mervyn Stone, ‘Plain Assumptions and Unexplained Wizardry Called in Aid of ‘The Fiscal Effects of Immigration to the UK’, December 2013 http://www.civitas.org.uk/pdf/assumptionsandwizardry.pdf; Robert Rowthorn ‘A Note on Dustmann and Frattini’s Estimates of the Fiscal Impact of UK Immigration’, April 2014 http://www.civitas.org.uk/pdf/rowthorndustmannfrattini.pdf; Robert Rowthorn ‘Large-scale Immigration-Its economic and demographic consequences for the UK’, August 2014 http://www.civitas.org.uk/pdf/LargescaleImmigration.pdf